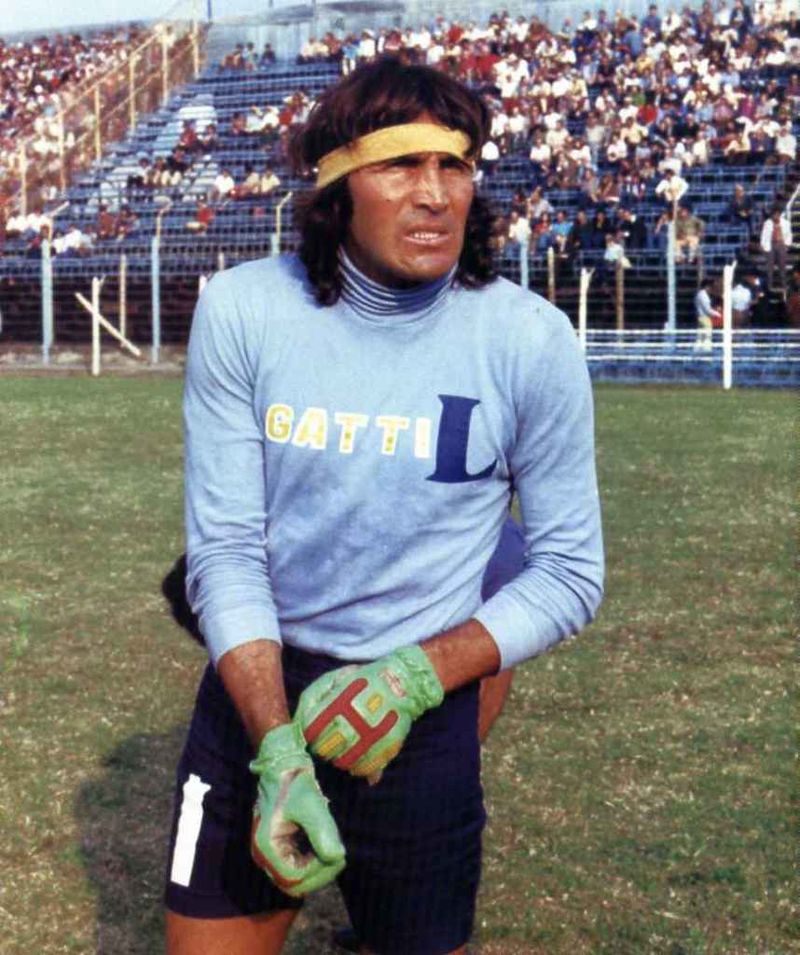

No other Argentine goalkeeper embodied the spirit of calcio spettacolo quite like Hugo Orlando Gatti. With his trademark headband, flamboyant jerseys, and unmistakable style, “El Loco” passed away at the age of 80 on April 20, 2025.

The Beginnings

Hugo Orlando Gatti (born August 19, 1944, in Carlos Tejedor, Buenos Aires) was one of the most iconic and revolutionary goalkeepers in Argentine football. Raised in the Atlanta youth system, he paradoxically began his sporting career as a forward during his youth. From the outset, he displayed an extroverted and flamboyant personality, earning the nickname “El Loco” (“the madman”) due to his charismatic, audacious, and often unconventional style. He wore long hair held back by a headband (vincha) and sported brightly colored jerseys—a youthful and bold look that, according to Argentine media, stripped the goalkeeper position of its traditional “solemnity and starch.” Gatti delighted fans with his theatrical presence on the pitch: he carried himself with irreverence and ease, yet managed to play 765 matches in Argentina’s top division across 26 seasons.

Following his retirement, Gatti remained a public figure, dividing his time between Argentina and Spain, where he worked as a television pundit and continued to make headlines with his provocative commentary. Gatti passed away on April 20, 2025, at the age of 80 in Buenos Aires, following a two-month hospitalization for a hip fracture and pneumonia, which ultimately led to multiple organ failure. The news of his death shook the football world: Boca Juniors paid tribute to him as an “eternal idol and multi-champion,” bidding farewell with a moving message: “Hasta siempre, Loco!”

Gatti joined Atlanta’s youth academy in the late 1950s, coming from his hometown. Despite initial difficulties—he conceded several goals during his trial and thought he had failed—the coaches saw his potential and kept him on. Hugo made his top-flight debut at the age of 18 in 1962, guarding the net for the Villa Crespo-based club for three seasons. With the “Bohemios,” he made 38 league appearances, standing out for his acrobatic style and uncommon confidence for someone so young. His performances quickly drew the attention of major clubs: in 1964, the powerful River Plate acquired him in a move described by the press as “the most expensive transfer in the history of Argentine football” at the time.

The career

In the mid-1960s, Gatti moved to River Plate, where he had the opportunity—and burden—of training alongside Amadeo Carrizo, the legendary goalkeeper of the Millonarios and his childhood idol. River saw Gatti as Carrizo’s natural successor, the latter having been a pioneer in modernizing the goalkeeper role. During his four seasons in Buenos Aires, Gatti made 77 league appearances with the red-and-white jersey, alternating in goal with Carrizo during the latter’s final years. Seeking more consistent playing time, Gatti left River and joined Gimnasia y Esgrima La Plata, where he tallied 244 appearances in the Primera División. In 1975, he signed with the ambitious Unión de Santa Fe. Though his stay was brief, it proved significant. Following a string of excellent performances, he was recruited by Boca Juniors’ newly appointed coach the following year, who brought his trusted goalkeeper with him to Buenos Aires. Thus, in 1976, Gatti joined Boca, the club that would ultimately immortalize him.

The 1980s were a challenging period for Boca, marred by financial instability and inconsistent results, but Gatti remained a fan favorite and a team icon. Despite periods of inactivity and rotation with younger goalkeepers, “El Loco” continued to defend Boca’s goal well beyond what was considered a reasonable age at the time. His final official appearance came on September 11, 1988: during that match, a failed dribble attempt in his own area led to a goal for Deportivo Armenio. That mistake effectively marked the end of his long playing career. The coach permanently replaced him with the young Carlos Navarro Montoya (who would himself become a legendary Boca goalkeeper), and Gatti never returned for another official match. A few days later, at 42 years old, Gatti announced his retirement, closing the circle in “his” Bombonera. Over twelve seasons with Boca Juniors, Gatti played 381 league games (417 in all competitions) and even scored one goal. He still holds the club record for most appearances by a goalkeeper and ranks second only to Roberto Mouzo for total matches played for Boca.

Despite his extraordinary club career, Gatti never achieved a comparable role in the national team, largely due to fierce competition from other top goalkeepers of the era. During the lead-up to the 1978 World Cup in Argentina, he vied for the starting role with Ubaldo “Pato” Fillol of River Plate. Coach Menotti appreciated Gatti’s qualities and even considered him the likely starter, but a knee injury just months before the tournament dashed his hopes. In the end, Fillol was selected and became one of the heroes of the World Cup, while Gatti was left out of the final squad.

Historical context: the goalkeeper in argentine football (1960s–1980s)

To fully understand Hugo Gatti’s impact, one must consider the context of Argentine football from the 1960s through the 1980s. At that time, the goalkeeper’s role was viewed in a far more traditional manner than today. South American “guardametas” were typically solid players focused primarily on shot-stopping and positioning, rarely engaging with the ball using their feet. There was an unwritten rule that goalkeepers should wear muted (often dark) colors to distinguish themselves from the referee and avoid clashing with their teammates’ bright kits. Heavy leather gloves and padded gear were also the norm—remnants of a slower, more physical style of football. An exception to this model was Amadeo Carrizo, whose pioneering approach inspired Gatti to push the boundaries of what a goalkeeper could—or should—do.

Gatti is remembered above all for revolutionizing the way the goalkeeper position was played. In an era when the prevailing wisdom was that “the chubby kid who can’t play” ends up in goal, Gatti completely shattered that stereotype. Technically, “El Loco” emphasized positioning and anticipation over sheer athleticism: he solved dangerous situations with intelligence and finesse rather than raw explosiveness. As noted by contemporary journalists, “he didn’t dive or fly unless necessary; he only made spectacular saves when essential”—a stark contrast to many of his peers, who often dove theatrically even for routine saves. Gatti believed the role of the goalkeeper should be played, not merely endured.

Many of his techniques became legendary. For example, he invented a unique one-on-one save technique dubbed “the save of God” by fans: Hugo would suddenly drop to his knees with arms spread wide, covering as much of the goal as possible and cutting off the shooting angle.

His presence marked the beginning of a stylistic “civil war” between the posts: on one side, the classical school embodied by figures like Antonio Roma (Boca’s stoic No.1 of the 1960s) and later Ubaldo Fillol in the 1970s (athletic but tactically disciplined); on the other side, there was Gatti—unpredictable, theatrical, revolutionary. The Gatti vs. Fillol rivalry dominated discussion for nearly a decade, sparking heated debate among fans and pundits alike: was it better to trust Fillol’s reliable sobriety, or Gatti’s mad genius? In Argentina, this gave rise to what some described as the first true “grieta bajo los tres palos”—a polarizing divide over the goalkeeper’s role.